Timeless Books Continue to Create Wonder

Philosopher, essayist and poet George Santayana once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Now, before you just trash this piece as some pompous young man in an ivory tower spouting enough excrement to show through his teeth, hear me out. I quote Santayana for a purpose and not to get the old, rotting soapbox out and preach a sermon that will be only half-heard.

With the current feeling of what seems a craze culture, it’s easy to believe there are no answers to the questions that lie before us. College students, fully-functioning members of society, artistic snobs and societal rejects, and, my God, everyone else who has ever had a cohesive thought race through their skulls, have had similar questions.

What is the social norm and should I just go with it? Am I crazy? If so, is that so bad? Should we trust our government? What is war and what is it good for?

If I told you to picture where you might find some insightful information for the lives that we live, what would come to the forefront?

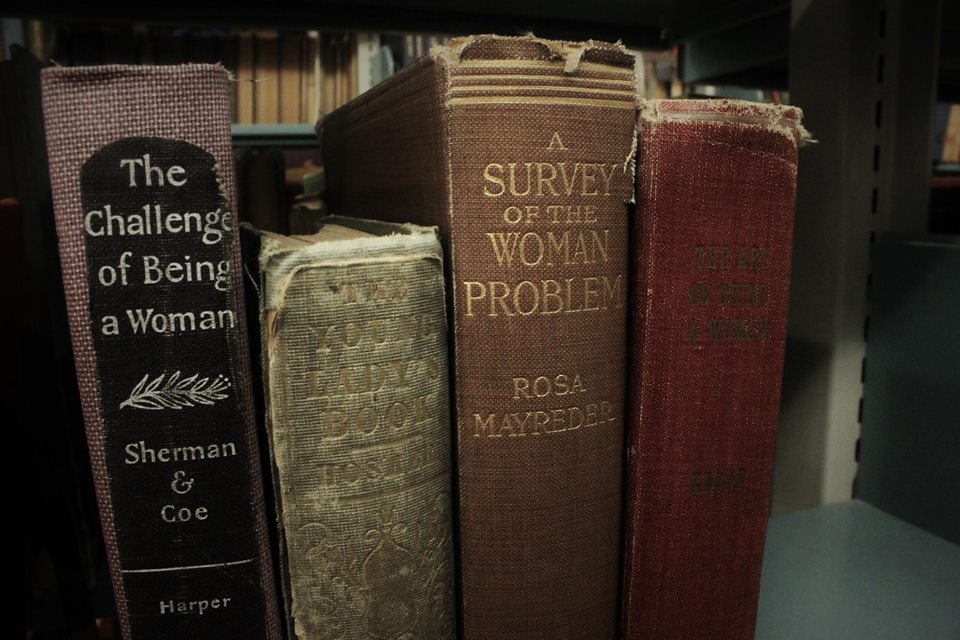

There, on the dusty shelves of your local libraries lie all the answers that you’ll need to know. Let me preface this list with something that I would want to read if I were reading this myself: No, I will not put any religious texts in this.

I’m in the business of writing and informing the public. Whatever God you believe in or don’t, I’m not here to sell a deity of any sorts.

So, without further delay, here is a comprehensive list made by the Pioneer staff, the Oklahoma Metropolitan Library System, and readers like you.

Mein Kampf: Adolf Hitler (1925) 720 pages

Do I have your attention? Good, you’ll need to pay attention as to why I had the gall to put this on the list. I don’t put this propaganda autobiographical novel on the list lightly. Written by Hitler while in prison after his famous failure political uprising in the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Mein Kamphf (My Struggle) outlines his poisonous political ideas and his future plans for domination.

Let me explain that his ideas to exterminate the Jewish race and the promotion of an Aryan race is evil incarnate, no question. But, in that same instance, why should we not read this book? It’s due to the social stigma that if you’re caught reading Hitler’s hate-filled book that you’re clearly in accordance with his white power movement. By that logic, by reading Harry Potter, I am automatically a wizard from Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Believe me, I wish. But, seeing as how reality still plays a massive part in our lives, let’s try to accommodate.

The political tactics used by Hitler can be found in many forms of modern politics. For example, President Trump banked on the American fear of losing their jobs and nationalism, President Obama used optimism and keywords like “hope” and “future”, and President Bush used the reaction of fear against terrorism. It’s these old political tactics that even a maniacal madman could use to convince its people of a future yet to be told. More to the point, society needs to value the lessons of history as they present themselves in order to learn from them. In order for us to battle evil, we must first recognize it for what it is. That is why it’s important to read Hitler’s work in its entirety. To live right and do the world justice is to learn from the faults of the past.

Catcher in the Rye: J.D. Salinger (1951) 214 pages

Taken place in December of ‘49, it’s a story that follows the wayward trials of college student Holden Caulfield. Being kicked out of his school Pencey Preparatory Academy in the upper-parts of Pennsylvania, Caulfield explores the culture of mankind through society that doesn’t understand him. As a college student, the idea of being understood and rebelling against the notions of educational obligations and being a black sheep amongst a flock of fluffy whites isn’t anything unheard of. Salinger brings his character through the thick and thin of society and sees what comes out at the end. The novel explores isolationism, surviving as an outsider on the threshold of the known and what is left to be said, and what it means to be insane by today’s standards. With so much more to discuss, I’ll leave you with this: Read this while a sense of rebellious youth still lives in you. It’s worth the read, I promise.

P.S. If you don’t choke up near the end, I don’t wish to know your soulless ass anyways.

Lord of the Rings (Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and Return of the King): J.R.R Tolkien (1954) 1178 pages

To start this off, I’d like to give thanks to all the lifelong nerds that turned me onto this book whenever I wa just a child. More specifically, my Dad. Thanks Old Man, I really appreciate it.

Now let’s make these fan boy and girls proud.

Originally written in the form of one volume, Tolkien takes people through the literary ringer with this one. Not in a “oh God, why?” sort of way. The story starts with a young Hobbit at the ripe age of 50. I know what you’re thinking but 50, by Tolkien’s standards, is just dipping your big Hobbit toe in the waters of life.

Hell, the wizard Gandalf is as old time itself and was approximately about 2,019 years old by the end of it all. Anyways, the story picks up with Frodo, his companions Samwise Gamgee, Merry Brandybuck, and Pippin Took going on a journey to destroy the one ring that would and could bring about the destruction of the world that they live in. There’s nothing quite like a Dark Lord and a malice towards mankind to put a little pep in your step. Tolkien uses his characters to explore the natures of what is good and evil in this world.

Those that you might of as all-knowing can be at fault and what is known as evil might just be misunderstood. Not to mention, the ideas of sacrificing what you hold dear for the sake of others and sticking by your morals in the face of adversity.

1984: George Orwell (1949) 336 pages

“What you’re saying, it’s a falsehood. And they’re giving our press secretary, he gave alternative facts to that.”

What you just read was not an excerpt from Orwell’s dystopian novel. This was a quote from President Trump’s advisor Kellyanne Conway when she spoke to NBC’s Chuck Todd about Sean Spicer’s false claims to the press. In a novel that takes place in what was supposed to be the far future, Orwell’s characters Winston and Julia begin by working for the nationalistic society that predicates itself on three principles; “War is Peace”, “Freedom is Slavery”, and “Ignorance is Strength”.

Orwell explores the nature of blindly following a nation-state without questioning the powers that be. It’s not necessarily an unheard of practice in the history of mankind. Need I remind people of the Germans with the Third Reich? As well as his concept of “Doublethink” that basically morphs two words with contradictory meanings to help provide false evidence for an argument with no basis. In a parting fact, when Conway said “alternative facts” on national television, Penguin Books ordered a reprint of 75,000 copies to keep up with surging demand.

The Great Gatsby: F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925) 180 pages

“Can’t repeat the past? Why, of course you can!” This timeless quote that comes from the protagonist with an antagonists heart in the story, Jay Gatsby, perfectly summarizes the way of the world today. Not to put any stressing markers on this novel, but this book has predicted the future and the mentality of men once before. The Great Depression began in 1929 and with Fitzgerald’s description of some of the lavish partygoers that would drive drunkenly into the night with the wheels off the car, it seems as though Fitzgerald may have it right on the head. But more to the point, the motifs of the novel are eerily similar to some of the ideas that we have in the modern age.

For example, as a society, we express our desire for a lavish lifestyle without any moral repercussions. We value the past and wish that things were back to the way that they were before the chaos of now began to come about. What Fitzgerald portrays through his characters like Gatsby and Tom and Daisy Buchanan is that the faults of the world have always been about; it’s just a matter of what they’re dressed as and how we deal with them. To live in nostalgia is to keep your eye on the rearview mirror going full speed down a highway yet unknown.

To Kill A Mockingbird: Harper Lee (1960) 281 pages

One of the issues that have been part of the mainstream conversation of society has been, and maybe will be in the future, racism. It’s a story that follows the children of a Southern defense lawyer, Atticus Finch in the constraints of racist bigotry that has been predicated throughout multiple generations.

The children, Scout and Jem, must see the way of the world riddled by racism and present it to the reading audience through the eyes of innocence. Though this novel was in the crux of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, this novel still rings true through much of the nation. To say that this book will have the capability to end racism by its very words is just a tad on the the side of insanity; however, it doesn’t diminish the fact that to end bigotry, we must first become educated with what we don’t know.

For Whom The Bell Tolls: Ernest Hemingway (1940) 480 pages

“The world is a fine place and worth fighting for.”

This quote comes from the Ernest Hemingway novel after the first World War and in the midst of the second. The book depicts the horrors and the necessities led by the aspect of warfare. It’s set in the midst of the Spanish Civil War with Robert Jordan, an American in the service of the International Brigades and fighting in the republican guerilla warfare to fight the Fascists. As it’s labeled as a classical war novel, Hemingway’s portrayal of war should make even the bravest war-hawk shudder. Hemingway was a reporter for the North American Newspaper Alliance during this time and saw the manic mess that war creates. People will always view literature as they perceive it to be but Hemingway, though one of the manliest of all male writers, was even horrified by war. Before we go on talking about which enemy of the state we will attack next, perhaps the words of Hemingway will warn us of what may come.

Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs: Hunter S. Thompson (1967) 278 pages

Just barely making it on the list, we ride alongside Thompson in his investigative piece on the infamous Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Gang.

Push aside the graphic images you’d see on a rerun of Gangland and settle in to the hard stories and facts about something that has been labeled as a “menace to society.”

The problem with social stigmas that have been passed down through multiple generations is that they have this innate ability to corner with common thinking. Thus, the idea of the Hell’s Angels. As Thompson explores the origins of the motorcycle gang, the reader learns that they originally came from World War II veterans coming home from overseas only to find that they couldn’t just “get with the program”. As they began to congregate, they rallied with their motorcycles and lived their lives as an outlaw, coasting on the line of society and savagery. As times progressed and the ideas of the people did not, they were viewed as nothing more than ruggish thugs on a bike. So, if you can’t join them, beat their cars in with bats wrapped in chains and harass the village folk.

What Thompson describes is the rise of a free society and the comings of a criminal organization. Through this, he depicts that people you view as evil and harmful to society are often misunderstood. Instead of fearing and hating what we don’t understand, perhaps we should take a page out of Thompson’s book and begin to learn.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: Roald Dahl (1964) 192 pages

That’s right, get the Oompa Loompas out for a joy ride and let’s sail down the acid trip of a chocolate river that we’ve all come to know and love. I’m not going to even begin discussing the Johnny Depp version; we won’t have enough time or pages for me to fill that rant.

Before Gene Wilder took us into a world of pure imagination, it was first a book written by children’s novelist Roald Dahl. The acid trip of a novel takes places in a poverty stricken neighborhood in which a young Charlie Bucket participates in a search for eight golden tickets to meet the reclusive candy and sweets mogul, Willy Wonka. Once the arguably naughty kids and their bad parental figures, one by one the group diminishes through mishaps in the Chocolate Factory.

Once it’s just Charlie and Willy together, Wonka decides to have Charlie’s family live in the factory with him. Avoiding the absurdity of the entire story, there is one existential thought that is spoken throughout the story: Morality. Each of the children, with the exception of Charlie, represent one of the seven deadly sins. Perhaps this is the reason that we are initially programmed to deem these kids and the parents that bore them in the first place as genuinely god awful people. Dahl allows the reader to see their rise in infamy and their fitting downfall a they make their may throughout the chocolate factory. Be kind to all and, most importantly, take care of one another.

A Brave New World: Aldous Huxley (1932) 259 pages

I think it’s the dream of a future worth living that we are allowed to live a life imperfectly. In 1932, Huxley explored this very idea that we all fear when we think of the future of society. Should we trust the status quo? Should we trust, let alone like, our government? Should it be questioned? Set in the year 2540 A.D, the two main characters of Bernard Marx and Lenina Crowne decide to go on holiday from the advanced society that they live into what is called a “savage reservation.”

The society that Marx and Crowne (Marx and Lenina: pretty sure Communism nod, just saying) are from have technological advancements in thinking, procreation and anti-depressants. By that, I mean specifically that they genetically engineer children, allow for open, numerous sexual experiences (orgies on the daily, I’m not joking), and for the masses of society to take this drug called “soma” that works as an antidepressant.

“Better to have a gram than a damn,” is a mantra of the manically depressive in this novel. Huxley’s characters are consistently pushing the envelope of society to see what is acceptable.

Spoiler alert: it’s not much. Whereas the “savages” live in communities that have monogamous relationships, give birth the way that history has deemed it, where religions are still in high regard.

So us, essentially.

The taboo nature comes from Bernard when he begins to integrate with the savages and falls in love with their ideology of free-will. This book explores something that every philosopher and sociology professor, every stoner and rebel, and every person that has ever wanted the status to go to hell has ever thought of. It’s the idea that you don’t have to accept what’s normal. The idea that, if nothing else, we should accept ourselves for who we are and to hell with the status quo. If you think about it, Huxley knew back even in ‘32 that normalcy changes as much as the wind; the only thing that we must be is ourselves. No more, no less.