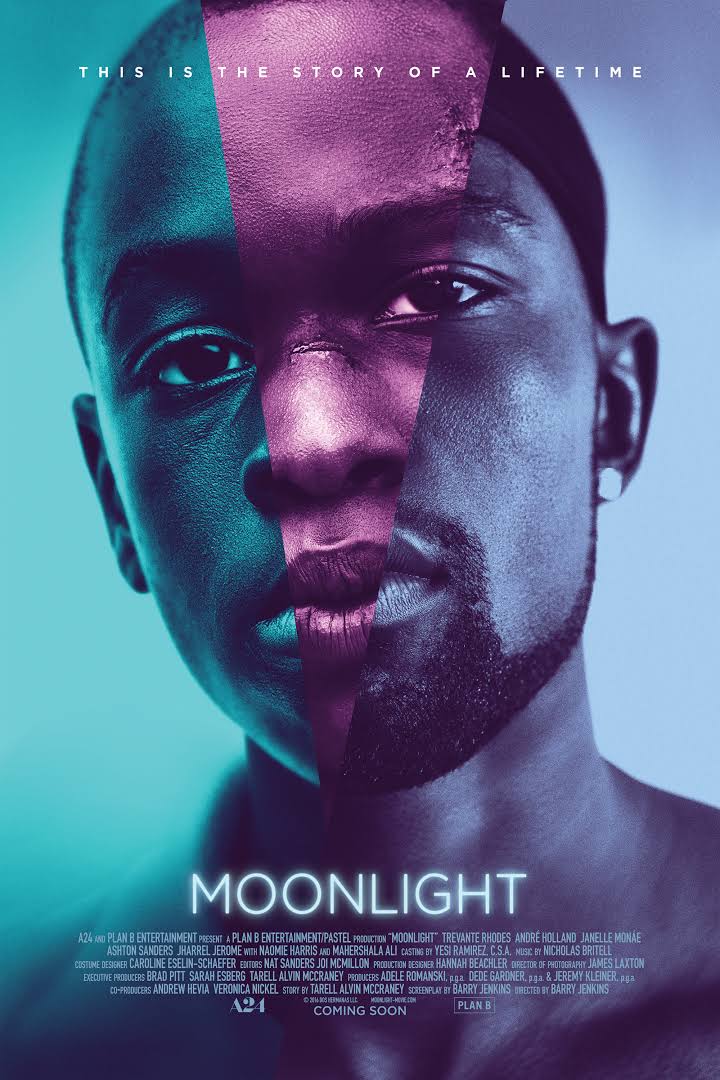

Movie Review: Moonlight

In the interior of a tricked-out low rider driving down a Florida highway, a young black man smiles and laughs. The passing city lights bounce off his gold teeth fronts with as much shine as his chrome rims.

“What… what you looking at me like that for?” Chiron jokingly asks Kevin, a man he has spent his entire life and had his first sexual encounter with.

Chiron drove from Georgia to Florida to see Kevin for the first time in a decade. Kevin looks at him sternly and says, “come on, man, you just drove down here?”

Chiron’s face drops to disappointment at the confrontation he hasn’t been ready to wrestle with his entire life leading up to this point.

“Moonlight” is a truly one of a kind coming-of-age film from the writer/director Barry Jenkins and based on the play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” by Tarell Alvin McCraney. Jenkins’ last film “Medicine for Melancholy” was released in 2008. He hasn’t lost his gift for showcasing pure human emotion in 24 frames per second. “Moonlight” stands as the visual antithesis of his last film.

The film follows Chiron as a young child, teenager and eventually ends with him as an adult. This sounds like any other coming-of-age story that John Hughes did numerous times in the ‘80s — except Chiron is a gay, black male growing up during the “War on Drugs” era in Miami, Florida. This makes a world of difference when you consider the problem with a reliance of hyper masculinity in the black community. The personification of this resides in a school bully that shows up in the 2nd act. He is vocal on campus about disapproving of Chiron’s entire persona. From his closeted sexuality and his tight jeans, the bully makes his juvenile rejection of him known.

The black community has historically usually not been inviting of gay culture and Chiron is the embodiment of the frustration and sadness that comes from being birthed into a culture that is already deemed to judge and dismiss him. Hip-hop culture, especially in the 1990s, provides a glowing example of this.

Hip-hop has thankfully become fairly more politically correct when it comes to other’s sexual orientation or personalities in the past decade. It was a culture that started out based around the fundamentals of having to look a certain way and if you didn’t, you were dissed and ridiculed into obscurity. Look at any of the monumental diss tracks in hip-hop’s history from “The Bridge is Over” by Boogie Down Productions to “Ether” by Nas. Gay slurs overtly flourish from almost every line to belittle, demean and ridicule the opposite person.

Chiron’s struggle may seem intended only to reach out to the small minority of gay, black men, but its reach goes far beyond sexuality, skin tone or social status.

It’s a mesmerizing take on existential turmoil and identity. What it means to find yourself, and what you discover about yourself when you don’t.

Kevin plays a Barbara Lewis track on a diner jukebox that reminds him of Chiron. The glances that follow between them spill out more emotions than most screenwriters could spend their entire career trying to convey via dialogue. What the characters don’t say is almost more important than what it does say.

“Moonlight” is the rare film that depicts characters without exploitation or sensationalization. It demands your attention and its direction is structured in a way that resonates deeply with the audience well after the mesmerizing last frame.

It’s the type of film that unravels with such honesty in its storytelling that audiences have been seeking for decades. All of its idiosyncrasies culminate into one important detail that not every film is able to accomplish: its brutal and beautiful honesty help us explore the complex character of Chiron, who the audience may identify with more than they initially thought.