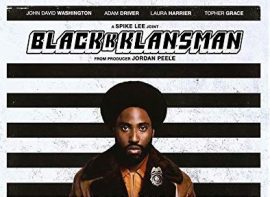

BlackKkKlansman is Thought Provoking, Intense

“Why don’t you wake up?”

The line—a response to BlackkKlansman’s main character, Ron Stallworth insisting that “America would never elect somebody like (KKK leader) David Duke president”—echoes internallyl well into the start of the next scene.

Director Spike Lee leaves no room for second-guessing his film’s message: BlackkKlansman is a movie about 2018 America, filtered through the true story of the first Black (emphasis on the capital “B”) police officer in Colorado Springs.

It is the early 70’s, and newly-minted detective Stallworth (played by John David Washington, firstborn son of House Denzel) has just spoken on the phone with the local chapter of the KKK. In a moment of inspiration, Stallworth enlists the help his partner Flip Zimmerman (played by Adam Driver) to infiltrate the Klan and gain intel from the inside.

Since Stallworth was the one who originally received the invitation over the phone, the two detectives agree to go undercover as two facets of the same character. The real Stallworth would continue to communicate with the Klan over the phone, using his “white voice,” while the more appropriately pasty Zimmerman would be the one who showed up in person.

The two quickly catch whiffs of a forthcoming plot against Black activists, and the investigation doubles down. The stakes are further raised when Zimmerman is suspected (correctly) of being Jewish. The unrelenting suspicion leads Zimmerman to realize that even though he isn’t Black, he still has “skin in the game.”

With Zimmerman’s realization, Lee tells his audience that in the fight against racism, nobody—no matter how white their skin—can afford to stay home. If you never leave the sidelines, your support doesn’t really matter. You aren’t helping.

Another prominent theme explored throughout BlackkKlansman is that of conflicting duality. Introduced in the film’s own title, the full extent of this question isn’t revealed until midway through, when Ron Stallworth is asked how he can rectify his skin color with his profession.

Is it possible to join a racially oppressive institution while remaining true to one’s Blackness? Does a Black cop forsake part of his heritage? Or is the very idea as incongruent and ridiculous as that of a Black Klansman?

Perhaps the mere validity of the question is the point. It is 2018, and Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter are on opposite sides of the picket lines. Until the division lines between the two coalitions are erased, that question will continue to hang in the air, buzzing around the head of every current and prospective Black police officer.

BlackkKlansman pays unique homage to its cinematic roots. Lee includes a scene featuring a Klan screening of D.W. Griffith’s 1918 film Birth of a Nation, a groundbreaking epic featuring the KKK as shining heroes. One of Griffith’s signature innovations in the film was the cross-cut; Lee interweaves that scene, via cross-cuts, with the retelling of a horrific 1916 lynching in Texas.

There is much to digest here. The Klan film-screening is bombastic and gleeful, while the lynch-mob recounting is somber and matter-of-fact. The righteous, high-flying rhetoric of white supremacy contrasts sharply with its ugly, brutal reality. Lee stands toe-to-toe with D.W. Griffith, and dismantles his masterpiece via the very technique it introduced to the world of film.

This ties into another overarching theme Spike Lee means to drive home with a sledgehammer: the racist factions in modern society may hide behind political rhetoric, and at-times downright hilarious stupidity, but their beliefs make them a potential threat to a truly free society.

After a brief intro montage, Lee opens up BlackkKlansman with comically ignorant racism—a well the movie draws from often in the first half. Alec Baldwin portrays the fictional Kennebrew Beauregard, a ranting buffoon who struggles to string together more than two complete sentences without a prompt to remind him of his rehearsed racism.

From then on, the movie’s Klansmen break up the monotony of cross-burnings and uninhibited streams of slurs with such acts of genius as drunkenly pointing loaded guns at their own heads.

But shortly after the audience begins to feel secure in the movie’s stable comedic relief, the director begins removing it. These imbeciles, as funny as they can be, also commit domestic terrorism and attempted murder.

By the end of the film, Spike Lee has made this point and highlighted it for emphasis. He closes BlackkKlansman out having left the story of Ron Stallworth behind in the 1970’s, and instead shows raw footage of real events from last year’s Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. Interspersed are clips of the real David Duke, President Trump, and a tribute to murdered counter-protester Heather Heyer.

The audience is left with one final image: an upside-down American flag, accompanied by silence. A distress signal; a battle-cry.

“Why don’t you wake up?”